One hot afternoon in the summer of 2016, the loud piercing sound of gunshots interrupted what should have been a lazy ride to the Jersey Shore for many travelling on the Atlantic City Expressway. What quickly unfolded in broad daylight on an otherwise serene roadway was a rolling gun battle between two rival drug factions. Two males in a black pick-up truck came up upon a white SUV and opened fire. The occupants in the SUV returned fire, and for several highway miles a shootout, reminiscent of a Hollywood action movie, played out on the eastbound lanes of the expressway. When it was all over, and the SUV came to rest at a nearby convenience store off the highway, one man was killed, and four others were injured. It was later learned that the driver of the black pickup truck had also been shot but was able to drive himself to a hospital in Philadelphia. For the New Jersey State Police (NJSP) making sense of this expansive crime scene, conflicting 911 calls, disparate witness statements, the body of the deceased, discarded weapons, and multiple shell casings belonging to four different weapons including a high-powered automatic rifle would surely be a challenge.

The rapid identification and arrest of perpetrators is what investigators strive for in order to stop armed criminals before they can do more harm, and by all accounts as we will later learn the above investigation was textbook in that regard. So often, because the cops are always on to another caper, we often don’t take the time to “rewind the tapes” and learn why investigators are successful in some instances and unsuccessful in others. In short, what would make the NJSP successful in this investigation – in addition to their skilled detectives – was the rapid access to critical pieces of information, from disparate sources, that they could essentially layer upon one another to make sense of an otherwise complex and confusion crime.

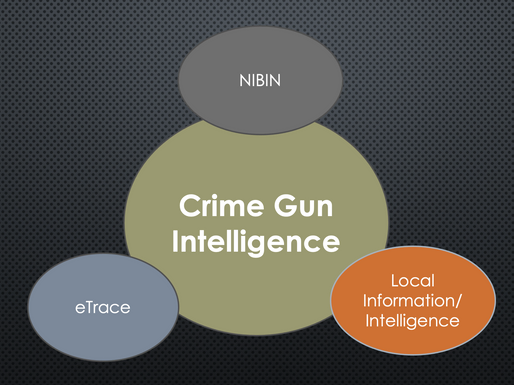

What is Crime Gun Intelligence?

Intelligence is one of those often-misunderstood terms that is thrown about in the lexicons of the military, law enforcement, and public safety. While it is outside the scope of this primer to define intelligence, it is worth noting that at the most fundamental level, intelligence is about understanding problems, and “really good” intelligence is about being able to do something with that intelligence. With that as a backdrop, crime gun intelligence (CGI) is the combining of investigative and forensic information to help investigators, analysts, commanders, and prosecutors better understand a particular shooting environment, while at the same time providing the actionable investigative lead information that can be used to further an investigation or prosecution.[1]

The Building Blocks of Crime Gun Intelligence

Those applying CGI to better understand the armed criminal environment draw their information sets from three basic building blocks or major areas that include: the National Integrated Ballistic Information Network (NIBIN), Electronic Tracing system (eTrace), and local intelligence sources. NIBIN, hosted by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) is a national database of digital images of cartridge cases that were either collected as evidence from crime scenes or test fired from seized crime guns. NIBIN can help police connect crimes, guns and suspects.

Additionally, ATF’s eTrace offers a systematic way of tracking the transactional history of recovered crime guns from its manufacturer or importer and ultimately to the last known retail purchase from a federally licensed firearms dealer. The eTrace system can help police generate crime gun intelligence of tactical and strategic value. Tactically, it can help police follow the path of a murder weapon right into the shooter’s hands. Strategically, it can help law enforcement officers and policy makers better understand the crime gun market in their area and uncover black market gun trafficking schemes.

Lastly, the local intelligence area consists of law enforcement information and criminal intelligence sources, specific to a jurisdiction or region, which can run the gamut. This CGI component can be furthered divided into three subcomponents: a) local law enforcement information, b) other forensic data, and c) additional technologies to be layered and leveraged. Local law enforcement information includes data and information from records management systems (RMS), information from police reports, field interview cards, informants, other law enforcement records systems (i.e. motor vehicle, court, probation/parole, etc. Other forensic evidence includes information related to DNA, latent fingerprints, trace evidence (e.g. blood, hairs, fibers, etc.). Technologies to be layered and leveraged includes data and information related to license plate recognition (LPR) systems, commercial and home security cameras, acoustic gunshot detection systems, facial recognition systems, credit card and cell phone tracking data, etc. A particular jurisdiction’s capabilities and policies will determine what is accessible to investigators as it relates to this important crime gun intelligence element.

The more CGI building blocks the better it is for a law enforcement organization charged with preventing, investigating, and prosecuting gun violence. CGI can be many things, sometimes just a single piece of information can be the case breaker, and what that case breaker looks like may well be different from case to case. However, most often, the break will come from a combination of pieces of information and intelligence, which act like steppingstones used to cross a stream. One never knows which piece will be the key one to break the case, so organizations must strive to develop an array of CGI elements. NIBIN and eTrace, both hosted by the ATF, are firearm specific in their scope, but it is the local intelligence component that is much broader in nature. It is its diversity that makes it so powerful, yet, most police agencies have to overlook it because they lack the right smart technologies to exploit and associate the disparate pieces of data. However, with the right solutions local intelligence that can be the great enabler for law enforcement organizations because it can provide context, visualization of the criminal environment, and a common operating picture for stakeholders to share information and collaborate.

Contextual Value

For those agencies engaged in investigating gun crime, the ATF’s NIBIN program has been a vital element. The technology can rapidly link fired cartridge casings to one another, thereby associating different incidents and crime scenes and the guns involved with the end result of providing more investigative leads for investigators to follow up on. Agencies that have refined their ballistic evidence collection and processing protocols have increased the amount of NIBIN leads they generate. This becomes a double edge sword, when agencies are unable to follow up or even prioritize the abundance of NIBIN leads they themselves are generating. Hence the reason why local intelligence is a critical component to the CGI concept. Local intelligence can provide context to better evaluate each NIBIN hit on its own and within a group

While the NIBIN system is a keystone to a strong violent crime suppression capability, it seldom stands on its own. Its limitations center on its inability to consistently provide contextual information to enable investigators to triage the “NIBIN Leads” it provides. In fact, agencies that solely rely on NIBIN to address gun violence are quickly overwhelmed with the deluge of information they encounter particularly if they are in a jurisdiction that has a history of gun violence. Yet, agencies that have used local intelligence – through protocols and technologies – to prioritize their “NIBIN Leads” find that they have a better handle over their crime gun intelligence capabilities.

The underlying reason of why local information and criminal intelligence is desperately needed to understand and triage NIBIN leads has to do with the very nature of these leads. NIBIN leads essentially come in two forms. A NIBIN lead that links a recovered firearm to a crime or series of crimes (“gun to crime”) in and of itself provides investigators with an easy path forward. However, those NIBIN leads that link two or more crimes together (“crime to crime”) are different – as they are not as “ready for prime time.” These leads require additional analysis – against the backdrop of local information and criminal intelligence – to better interpret and understand the common denominators between them. In just about every jurisdiction that is plagued by gun violence, it is the “crime-to-crime” NIBIN leads that represent the overwhelming majority of the agency’s leads.

Unfortunately, many law enforcement agencies that participate in CGI efforts are only following up on the “gun to crime” NIBIN leads because they do not have the smart technological and analytical capabilities to address the larger amount of “crime to crime” NIBIN leads. These agencies feel like they are drowning in the morass of raw crime-to-crime NIBIN leads because very little follow up is done to triage or prioritize these types of leads. Smart technologies that offer a visual backdrop showing the contextual relationships between “crime to crime” NIBIN leads and their underlying associations can increase the amount of follow up that is conducted on the “crime to crime” NIBIN leads.

For the NJSP, in the Atlantic Expressway Shooting investigation outlined above, what they relied on to understand the shooting incident was the visual representation of the relationship between NIBIN, license plate reader (LPR) information, cell phone tracking information, and criminal intelligence. Analysts from the state’s fusion center aided detectives by providing additional layers of information to help piece together the crime, and then locate, and apprehend the offenders. What this agency demonstrated is that with the right mindset, the right information, and the right software solutions to deliver that information to the folks that need it in the moments that mater the most investigations can be culminated in a swift and effective manner.

Visualization

The average person – and for that matter, the average investigator – tends to be visual in terms of the way in which they prefer to process information. Anyone familiar with conspiracy investigations has seen hand drawn diagrams plastered all over the walls of wire intercept room, so investigators can better understand the relationship of those that they are investigating. Understanding this touch point has compelled successful investigators and analysts to explore innovative ways to illustrate the critical associations between the people, places, and things that are all linked to crimes. As it relates to CGI, particularly because the abundance of investigative and forensic information, it becomes paramount for line level investigators to have rapid access to link- association technologies that can illustrate the associations that translate into leads.

Additionally, in the above description of CGI, the core elements are sorted into three buckets. However, it is that last bucket, local information and intelligence, that becomes a bit more complicated for investigators to pour out in their heads. Technologies that allow for the layering of data sets offer investigators opportunities to customize what associations, whether many or a few, they want to see in order to understand the often hidden and complex associations needed to further investigations.

In the Expressway shooting investigation, the NJSP utilized link-association technologies to map shooting events, ballistic evidence, and LPR data. That visualization of data allowed for investigators to rapidly understand what would otherwise be complex scenarios.

Common Operating Picture

A robust CGI capability requires both informal and formal partnerships among diverse entities. In other words, patrol officers, detectives, analysts, ballistic and forensic technicians, commanders, and prosecutors must all partner and think and act together to share information and insight. More specifically, these stakeholders must develop a shared purpose, shape that shared purpose via policy, and then develop protocols to implement and adhere to those policies in order to realize the overall shared vision. The reason these independent stakeholders need to communicate, coordinate, and collaborate becomes even more apparent is when one is asked to think of the amount of time a line officer or detective actually gets to speak with a ballistic examiner or DNA technician. The answer is hardly ever. While it is critically important that each of these entities described above performs a specialized function, the nature of policing or investigations does not often allow these individual disciplines to communicate day-to-day to develop critical information sharing relationships. Add to the mix, these same entities communicating with prosecutors the examples that come to mind are further reduced.

An agency’s ability, or a multi agencies’ ability as in the case with real-time centers and fusion centers, to share an illustrative depiction of the criminal associations between persons, places, and things across a diverse stakeholder community is crucial for defeating gun violence. Providing a common operating picture built around a shared purpose to these stakeholders that may all have a slightly different role in the investigation, or their specific law enforcement mission offers them opportunities to leverage each other’s insights and capabilities. With smart technologies, a common operating picture can be shared across jurisdictions or disciplines. For example, investigators in the field, ballistic technicians, criminal analysts, and prosecutors can all see the same associations uncovered in an investigation, while at the same time offering insights that only their disciplines would know.

Conclusion

Whether violent gun crime is surging in a particular jurisdiction or shooting events are few, the expectation by the public is the same: investigations and prosecutions must be swift, effective, and efficient. Bringing justice to the victims, resolution to their families, and peace to affected communities requires the right balance of people, processes and technology.[2] All “people” involved must think and act together across agencies and jurisdictions, the processes involved must be policy driven, and the relevant technologies must be layered and leveraged.

Having the technological ability to layer, associate, and map the diverse elements of CGI that include a) NIBIN data, eTrace data, and most importantly a jurisdiction’s local intelligence provides investigators, analysts, and prosecutors the ability to draw associations in fact that further both investigations and prosecutions. Additionally, this type of technology is indispensable for commanders to proactively design strategies and operations to suppress violent crime. When this technology is combined with sound policy, good leadership, and robust training programs those charged with combating violent crime increase their chances of success exponentially.

The expressway shooting above is one example of how by providing context, the vital ability to visualize information, and an effective way of sharing it, detectives can turn a chaotic mess on the highway into a successful outcome. After a few days, the investigative team rounded up all suspects on charges of conspiracy to commit murder, murder, weapons offenses, and gang criminality. A year later, the one defendant plead guilty to murder and the others to their individual weapons offenses. More importantly, violent criminals were taken off the street so as not wreak havoc on the highways or their own communities. Great job by the NJSP, who, like other law enforcement agencies globally, are working with technology providers to explore and implement better ways of combating crime in more efficient and effective ways.

[1] Note: For some additional discussion on CGI see Gagliardi, Pete. “In the Crosshairs: Crime Gun Intelligence.” The Police Chief 85, No. 7 (July 2018). http://www.policechiefmagazine.org/in-the-crosshairs/?ref=1d245accbc2dba02e0503c239aa645f6 [2] ibid